EXploring Vanity

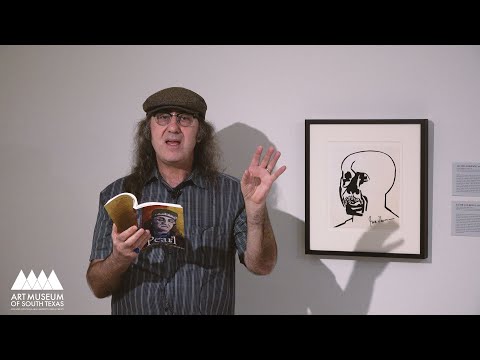

Eye to I - Online Programming

In Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, the character Mary explains that “Pride relates more to our opinion of ourselves, vanity to what we would have others think of us.” Inspired by this sentiment, AMST invited Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi professors to explore the relationships between artists, vanity, and self-portraiture. Through the lenses of their research and the art in the exhibition, Eye to I: Self-Portraits from the National Portrait Gallery, Dr. Pamela Brouillard presents her audio essay “The Reflected Self” and Professor Tom Murphy reads his poem “The Last Days of Cherry.”

“Pride relates more to our opinion of ourselves, vanity to what we would have others think of us.”

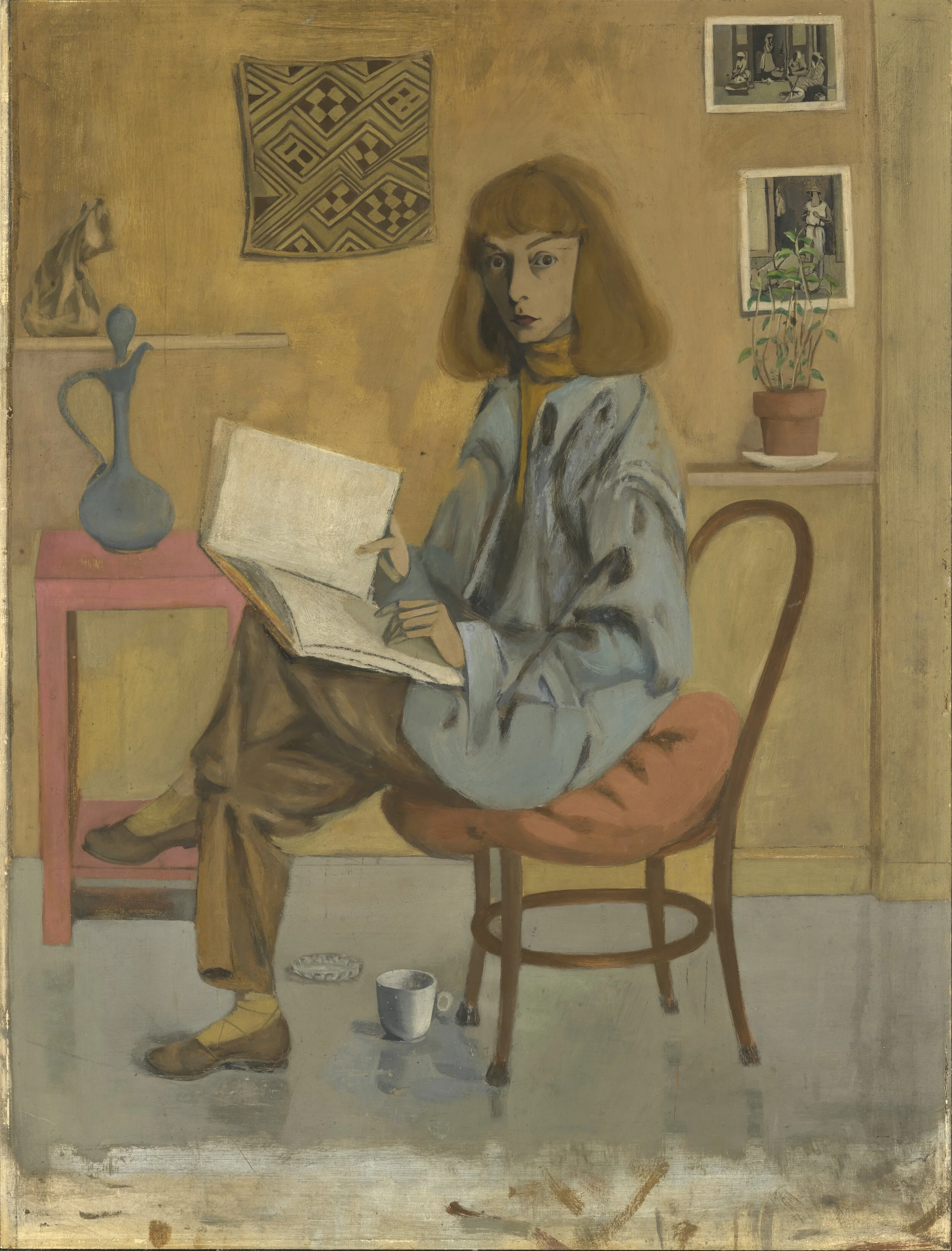

Lee Simonson, Lee Simonson Self-Portrait, c. 1912, oil on canvas, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of Karl and Jody Simonson; frame conserved with funds from the Smithsonian Women’s Committee

LISTEN

Dr. Pamela J. Brouillard

Regents Professor of Psychology (TAMU-CC) Specializing in:

Health disparities and the psychological factors that impact health behaviors

The Reflected Self: Visual Insight and Imagination in Self-Portraiture

The psychologist Carl Jung believed that the self was divided into multiple parts - some of which were more transparent than others. While Jung’s theory has limited application in psychological science today, one of the most enduring aspects of his work is its contribution to understanding cultural forms and the aesthetics of the visual and literary arts. Jung believed that the aspect of self that was most often revealed to others was the “Persona” - the social face that we display in public, often mask-like in nature and concealing of true identity while at the same time revealing how we are seen in the world. More integral to Jung’s theory was his notion of the “real” self – a more cohesive and true representation of our emotional lives which unifies the many aspects of self as part of a mature developmental process which he called self-actualization and is revealed through images and symbols of meaning to the individual.

The current traveling Eye to I exhibit at the Art Museum of South Texas is a beautifully curated and diverse collection of self-portraits by American artists from the National Portrait Gallery in Washington D.C. that offers insight into the maturation and development of artistic self-representation from the directly personal to the deeply symbolic across multiple mediums. As you move through the exhibit you will find images and objects that vary from simple line drawings to complex and highly symbolic representations of both the artists and their craft – images that fall across the continuum from the persona to real self. As all self-portraiture is by its very nature self-reflective, given that the artist cannot “see” themselves and must use a reflected visual image - whether they are doing a traditional portrait or using a more symbolic image, these representations can never essentially be “true” as a complete, accurate and absolutely revealing image. They must by necessity be interpreted through the eye of the viewer for both meaning and emotional impact. Thus, they are interpersonal, intimate and often compelling as they reflect not only the artist’s intention but also the subjective experience of the viewer who uses their own personal experience to cast back against the image for meaning.

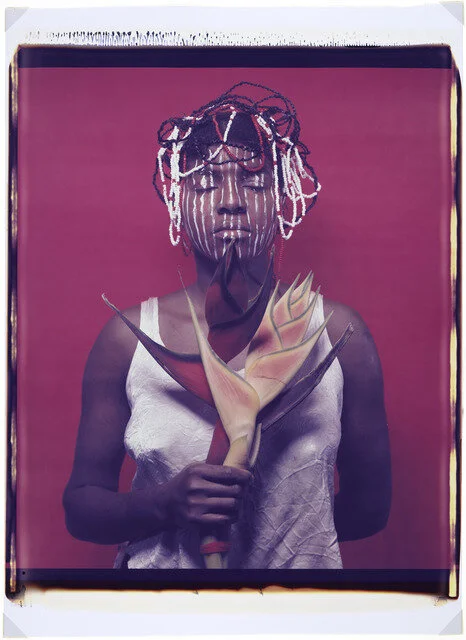

María Magdalena Campos Pons, Untitled from the series When I am not Here, Estoy allá, 1996, dye diffusion transfer print, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of Julia P. and Horacio Herzberg

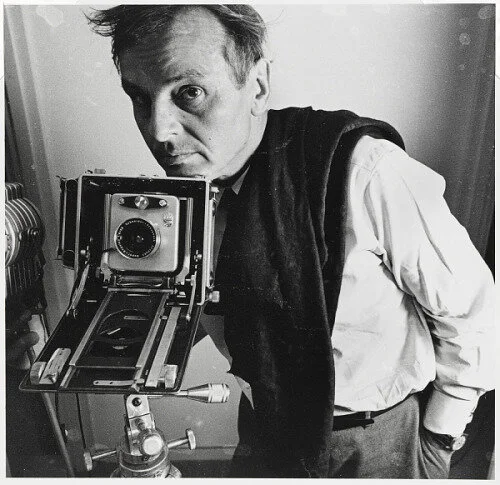

Whether more “realistic” or “symbolic” the images in the exhibit reveal both personal and public aspects of each artist’s persona. For example, in the lithograph of Mabel Dwight the tilt of her head signifies her reflective glance rendered against a dark shadowed background, her pen poised in the creation of her image. The portrait creates a feeling as if she is a friend – the black and white contrast focuses your gaze on her features more clearly without the distraction of color - refined and calming – she wants you to see her. In the black and white photograph of Hans Namuth the gaze is direct and forceful – the camera lens aligned with his eye, intimating a sense that the viewer is also being seen by the artist. The brilliant colors in the print by Maria Magdalena Campos-Pons demand that you see her color, the white headdress emphasizing a sense of spiritual transcendence, the exotic vermillion background echoing the flower she cradles.

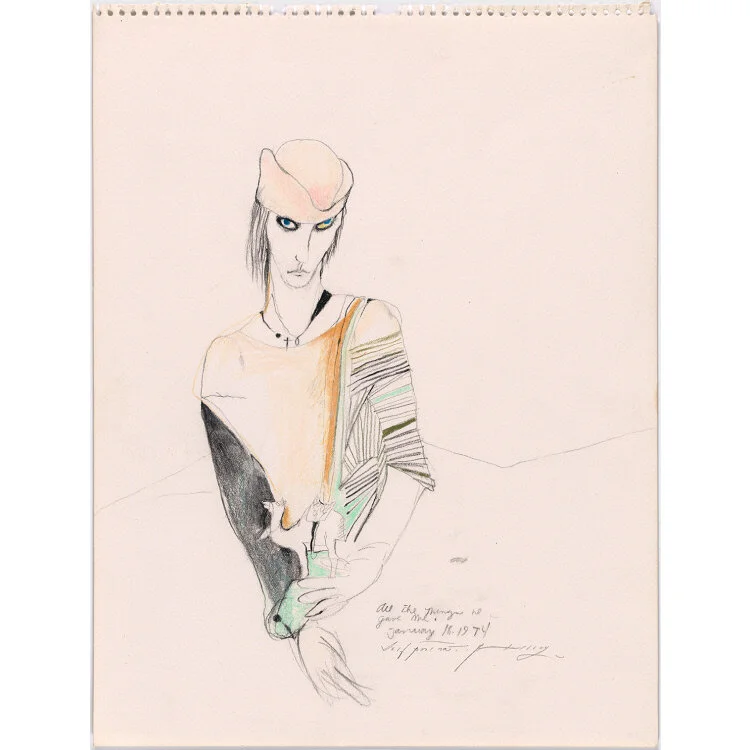

Patti Smith, Patti Smith Self-Portrait, 1974, graphite and colored pencil on paper, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; funded by the Abraham and Virginia Weiss Charitable Trust, Amy and Marc Meadows, in honor of Wendy Wick Reaves

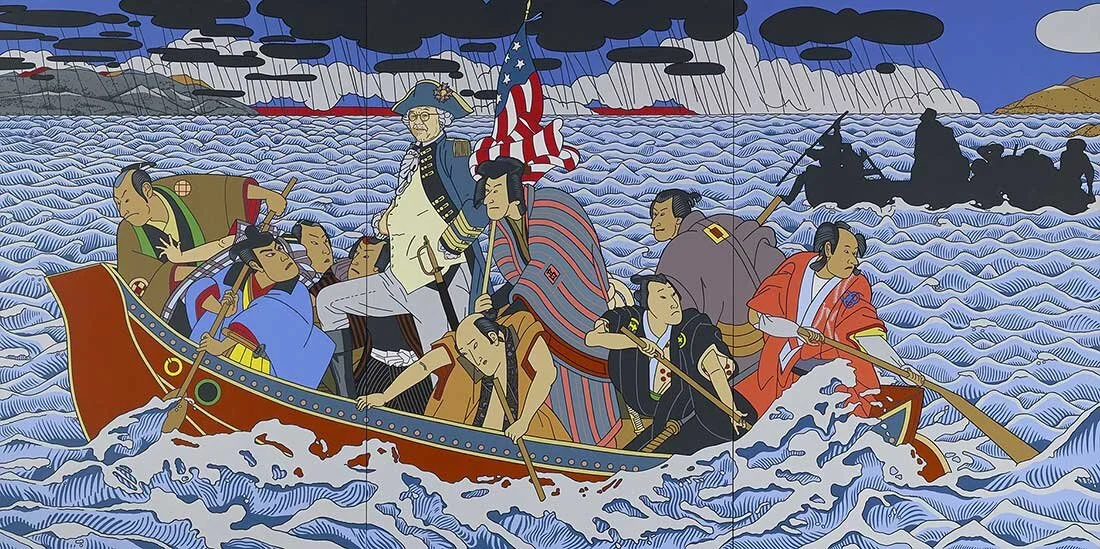

Roger Shimomura, Shimomura Crossing the Delaware, 2010, acrylic on canvas, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of Raymond L. Ocampo Jr., Sandra Olesky Ocampo, and Robert P. Ocampo

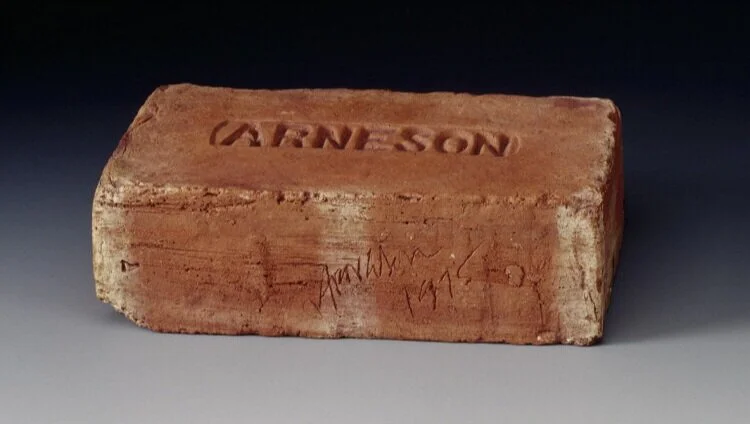

A highly stylized pencil drawing by Patti Smith shouts punk with brooding eyes, heavily lined, darkly drawing you into her as she cradles a childlike memento of lost love. Roger Shimonmura’s canvas is especially timely as it contrasts the symbols of American freedom against the background a traditional Japanese woodblock print – freedom is threatened by the brooding black clouds against the red, white and blue horizon – the choppy waves threaten to capsize the boat, the ghost image in the background is black as death. He asks us to see him and the precarious nature of his journey as an Asian American. Most evocative of Jung’s use of symbolism to denote identity is Robert Rauschenberg’s triptych of multimedia panels showing the artist laid bare to the bone, his life narrative unwinds in a spiral across the second panel, brought home to his birthplace in Port Arthur TX on the last panel. The most solid and literal self-representation of the artist as craft is Robert Arneson’s terracotta brick – his hand visible in the signature on its side; its weight solid and substantial, referencing a career exploring the use of ceramics as a vehicle of identity.

The works represented in this exhibition invites introspection and enhance our understanding of each artist’s work, as well as our understanding of ourselves. As a clinical psychologist, the viewing and interpretation of each of the images and objects in the exhibit provide many parallels to the process of psychotherapy in which the therapist gleans insight into the client through their reflected image – often juxtaposed against our own understanding of self as we tease out the truth from the information we are shown as projected against our own emotional landscape.

The truth is always relative of course – I invite you to explore your own truth as you explore the many extraordinary works found in the exhibition.

- DR. PAMELA J. BROUILLARD

WATCH

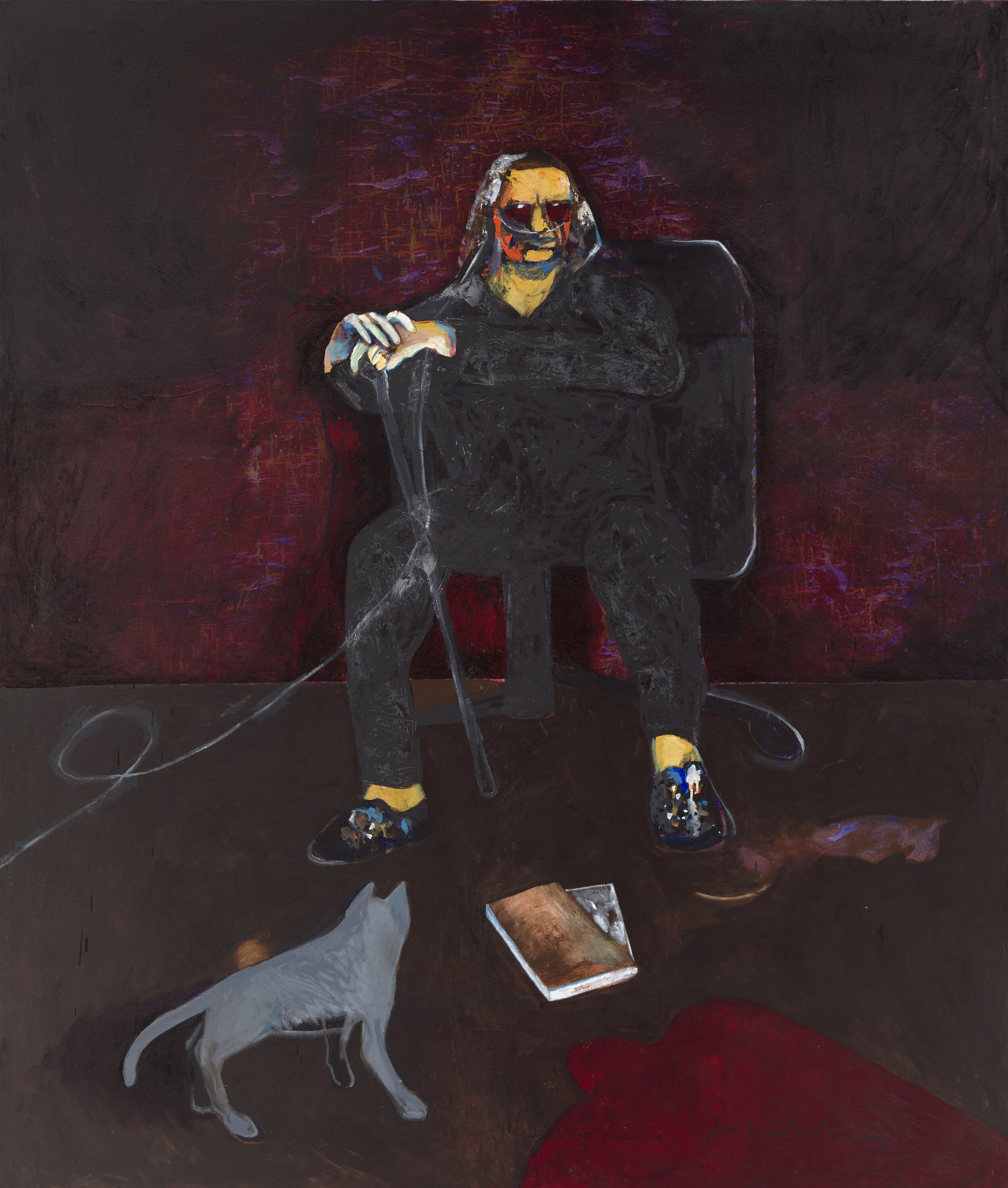

Fritz Scholder, Self Portrait with Grey Cat, 2003, 2003, oil on canvas, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

Pets and Personality

By including pets in their self-portraits, artists reveal even more of their own personalities. The glimpses into the artist/pet relationships, both universal and highly specific, give the viewers of Eye to I, insights into artist identities that visual likenesses alone could never accomplish. Tom Murphy's poem - imbued with the spirituality, weariness, and freedom of the Beat Poets - recounts the final days of his beloved cat's life, giving us an even clearer portrait of the poet himself in the process.

After you visit the exhibition Eye to I or watch and listen to Murphy's poem, we ask you to consider what the connections to your pets reveal about you?

Create

ARTISTS’ Vanities

This photo prompt and art activity will inspire you to create your own meta-commentary on vanity and self-portraiture.

First, take a photo of the mirror that you use to get ready before going out in public.

Using your camera settings or photo editing software change this image to black and white.

Choose an existing selfie that shows you in the manner that you would like others to see you.

If using photo editing software crop or clip the selfie into the same shape and proportions as the mirror in your first photo. If using traditional media print and cut the selfie to the same size and proportions as the mirror in your first photo.

Finally, cover the mirror in your first photo with the re-sized selfie to complete your photo collage.

Two useful questions to keep in mind while completing this photo activity are:

How might individuals manipulate their selfies when presenting them publicly?

Is everything you see on social media or a gallery wall an accurate reflection of reality?

Read

Elaine De Kooning, Elaine de Kooning Self-Portrait, 1946, oil on masonite, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

For Even More Information

Presented by: